How much should kids drink? Lifting the lid on sippy cups

Drink more water, we’re often told, But how do we gauge a baby’s thirst? Dr Anne Tait lifts the lid on sippy cups and their contents.

We’ve all heard the recommendations that we grown-ups should drink at least eight glasses of water a day. However, this is a myth, thought to be started in 1945 by the US Food and Nutrition board, and what a lot of people do not realise is that there was a crucial sentence missing stating that this amount of fluid includes liquid contained in our food. Other drinks such as tea, coffee and milk also form part of an adult’s fluid intake. Unfortunately, there really is no evidence that drinking more water will make your skin better, flush out toxins, or help you live longer, which is a bit of a shame for those of us getting older.

So that’s the theory for big people - what about the littlies? We have the saying in paediatrics that children are not little adults and this is certainly true in the case of fluid intake. Babies under six months of age do not need any additional water intake. Their daily fluid requirement is obtained from breast milk or formula. Breast milk is 88% water and that is enough for young babies. Giving young babies additional water at this stage can be risky, in that it can lead to a rare condition called water intoxication where the salts level in the blood can be diluted to such an extent that the body can go into seizures.

Babies aged between six and twelve months can be given small sips of water if they are thirsty (possibly 60-120ml per day), but again, most of a baby’s daily fluid intake will be obtained through breast milk, formula and solids. Exactly how much water they need is somewhat debated but certainly children this age should not be forced to drink water, rather it should be offered to quench thirst.

THIRSTY WORK

There is a very delicate balance in our body’s constant monitoring of our blood pressure and the level of salts in our bloodstream. Technically speaking, this balance (coordinated by sensors in our kidneys and brain) acts to alter our urine output and the amount of salts in our urine depending on our internal hydration state. It is therefore difficult to say how much fluid each person should drink, as that will depend on their size, food intake, other fluid intake, temperature of their environment, activity levels, age, gender, and other medical conditions they may have. However, my own thoughts are that most of us - adults and children - are generally pretty good at drinking when we are thirsty and that we don’t need to force ourselves to drink more fluids than we want.

One thing all the experts do agree on is that the best fluids for children are water or milk. Juice, energy drinks, coffee, tea and sports hydration drinks are all inappropriate for young people, despite what the drink marketers tell us. For older children, diluted juice may be an option for a small amount of fluid intake, but caution should be exercised, particularly around the risk of tooth decay and excessive weight gain. Eating a piece of fruit, as opposed to drinking juice, is a better option as you benefit from the fibre.

SICKNESS AND DEHYDRATION

It has been a very busy winter for us in the hospital with a lot of respiratory viruses about. When on call recently, I saw a number of children admitted for various acute medical illnesses and a number of these little patients were dehydrated as a result. When we are sick, we generally feel fairly miserable and not keen to eat or drink. This is particularly true for children and a common cause for hospital admission is poor feeding and/or dehydration.

When children are sick, we recommend offering them small but frequent sips of fluid. For babies under six months of age, they may need to be breast or bottle fed every hour, or even more frequently. If a child is refusing most or all fluids, then they do need medical assessment by a doctor. This is particularly pertinent if they are losing excessive fluid through fever, vomiting and/or diarrhoea.

Dehydration can occur rapidly in illness, especially in very young children, although babies and children do show recognisable symptoms as a helpful warning. Caregivers need to be very attentive to the symptoms and seek medical review promptly, but also repeatedly, if things get worse and/or don’t improve.

SIGNS OF DEHYDRATION INCLUDE:

🍼 Dry lips and/or tongue

🍼 Reduced wet nappies (although this can be difficult to determine if the child is suffering diarrhoea)

🍼 No urine for more than 6-8 hours

🍼 Dark-coloured urine

🍼 Irritable

🍼 Sleepy/lethargic

🍼 No tears when crying

🍼 Sunken eyes (somewhat late sign)

🍼 Cool extremities (fingers, toes and nose)

From a more medical perspective, we would be looking for all of the above signs but would also check for elevated heart rate and reduced blood pressure (a late sign of dehydration).

To prevent dehydration at home when your child is unwell, offer breast milk or formula, rehydration fluids (ie Pedialyte), diluted juice and water. It’s a good idea to offer more than just water to an unwell child, as there are no salts or energy in water. Keep a record of both fluid intake and urine output, while also keeping a watch out for signs of dehydration. Seeking an early medical review if there are any concerns is always advisable. Children can get sick very quickly, despite parents being aware of all of the above issues. My opinion in a consultation is a ‘snapshot in time’, and if parents feel that things are getting worse, they need to seek a follow-up assessment.

RAISE A GLASS

In summary, babies under six months do not need any additional water intake. Between six and twelve months, babies can be offered small amounts but most of their fluid intake is through milk feeds and solids. Children over one year old can drink to their thirst requirement. Generally, we’re pretty good at drinking the amount of fluid our bodies need, as being dehydrated is an unpleasant feeling we innately try to avoid. When children are unwell, however, they will often feed only in small amounts. This, coupled with increased fluid loss through vomiting, diarrhoea and fever, means children can get dehydrated very quickly. Offering small amounts of fluid frequently, noting urine output and recording fluid loss (ie frequency of vomiting and/or diarrhoea), and being watchful of the signs of dehydration are my main recommendations.

|

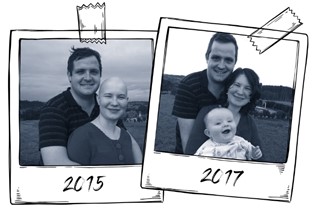

Dr Anne Tait is a general paediatrician employed at Starship Children’s Hospital who also works in private practice at Auckland Medical Specialists. She has an interest in all areas of children’s health and wellbeing. |

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 39 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW