Explained: Post Natal Depression is not the same as the 'baby blues'

General practitioner and urgent care doctor, Dr Isabelle Duck explains how postnatal depression is so much more than just the 'baby blues'.

Parenting-life is a turbulent existence of highs and lows, plus the day-to-day bits in between. The wiping of runny noses, changing of nappies, the feeding and the bathing, and constant tidying up. Not to mention the mountains of laundry! This season can be even more tumultuous if complicated by a traumatic labour, a premature birth, post-partum complications, or the birth of multiples. It’s hard to deny the huge chasm between one's life before and one's life after having a baby. All of a sudden, pre-baby life seemed so carefree and easy, now there’s a small human to nurture – it’s a huge adjustment.

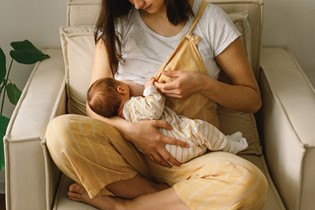

Some say that motherhood is a long series of emotional contradictions. The sadness of missing your old life versus the joy of a new family life; the misery of long sleepless nights versus the happiness of newborn cuddles; the distress when your baby falls and hurts themselves versus the excitement when they take their first steps.

Nevertheless, it’s the small triumphs that get us through both the difficulties and the mundanities. Some parents, however, are unable to enjoy these unique moments. And this sadness and worry can last for many weeks or months. If you are experiencing these feelings, it’s important that you visit your doctor, as it’s possible that you’re suffering from the symptoms of postnatal depression.

A discussion on postnatal depression is not complete without at first referring to the 'baby blues'. The baby blues are different from postnatal depression, and are an extremely common experience for new mums – affecting around 70-80% of women. The baby blues usually start around three to five days after the birth of a baby. The signs include irritability, tiredness, mild depression and tearfulness. The baby blues are caused by hormonal changes and feeling tired physically and emotionally after the birth of a baby. The baby blues are temporary, and usually settle within two weeks. They are considered a normal part of the emotional changes after the delivery of a baby.

Postnatal depression is different from the baby blues. Symptoms include (but are not limited to) intense sadness, hopelessness and anxiety, and last over two weeks. Many parents with postnatal depression find it very hard to find any joy in looking after their new baby.

They may be irritable, feel constantly tired and overwhelmed, and tearful. Some experience a loss of appetite and a low libido. Others feel guilty about not being happy about having a baby, and in contrast to the baby blues, postnatal depression symptoms typically do not go away. Postnatal depression is common, and affects one in eight women following the recent birth of a live baby. Postnatal depression can manifest for up to one year after the birth of a baby.

It’s important to note that other mental health conditions can sometimes mimic postnatal depression. Again, this highlights the importance of early medical assessment by your doctor or midwife. If you believe that you or anyone you know have the symptoms outlined above, or any other concerning symptoms, it is important to seek medical advice. The sooner this is done, the better.

As the age-old saying goes, “prevention is better than cure” – and there are sometimes things that can be done to help to a new parent's mental health. Whilst it is not always possible to avoid a difficult labour, postpartum complications, feeding challenges or a colicky baby, self-help measures can ease some of the unpleasant feelings. Do not put too much pressure on yourself, your house doesn’t always need to be immaculately tidy. Accept help from friends and family and try to take some time for yourself everyday, whether it's by having a lie down when the baby naps, letting a trusted adult hold the baby, or by booking yourself a massage. Spending time with supportive friends can be helpful, and coffee groups are also a good way to interact with other parents. When my daughter was a baby, I used to meet up with an amazing group of mothers who did not judge me if I had a milk-stained tracksuit on, looked exhausted, and had been up all night long. They had all been through the same at various times. I am also a real believer of getting out of the house; something as simple as popping the baby into the pram or the carrier and going for a walk is sometimes enough to lift your mood.

Sometimes, despite these efforts, postnatal depression cannot be avoided. In New Zealand, doctors and midwives are trained to screen for postnatal depression. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is one of the tools that healthcare professionals use to screen for this condition. It's a questionnaire which contains a series of questions relating to mood. Additionally, it is sometimes used to diagnose depression in a pregnant woman before their baby is born.

Postnatal depression does not distinguish between age, race or background. It can affect those with a history of mental illness or those without. Postnatal depression may manifest after the birth of a second or subsequent baby, whilst not being present after the birth of a first baby; or indeed the opposite.

So what can be done to help a woman who has been diagnosed with postnatal depression? There are many treatments available. Management depends upon the severity of the symptoms, and as with any illness, it is important that the woman is involved in the decision-making process. Treatments range from education on self-help measures (such as those outlined above), to counselling, to antidepressant medication. In some cases, a referral to the maternal mental health team or psychiatric services is indicated.

The decision on whether or not to take an antidepressant medication is an important one which needs to be discussed at length with your own doctor. In my general practice role, I have prescribed antidepressant medication for many mothers and some may be taken whilst breastfeeding. As with taking any medication, the pros and cons need to be discussed with the prescribing doctor. Things to consider include previous drug allergies, potential side effects, other long-term medical conditions, as well as other regular medications taken by a patient. As a rule, antidepressant medication must never be stopped suddenly without medical advice, and never take a medication which has been prescribed for another patient.

It is important to note that postnatal depression can also affect fathers and co-parents. As with many mental health conditions, depression in one partner can increase the risk of depression in the other. Fathers and co-parents often have the added stress of going back to work soon after the birth of a baby – this can be extremely challenging for some, especially when they are also getting used to their new parental role, the change in routine and the lack of sleep.

A diagnosis of postnatal depression is not a label that you are failing. Postnatal depression is a treatable illness, it’s not a reflection on you as a parent. It need not define you. And remember, it’s a sign of inner strength to ask for help.

We need to continue to break down the stigma associated with postnatal depression, so that parents feel able to speak out about their experiences without feeling judged. It is important to understand that postnatal depression is a very treatable illness, knowing this will empower new parents to visit their doctor and to ask for help.

I am now going to leave you with a wonderful quote about mental illness from Michelle Obama. I think this sums things up rather well:

“Whether an illness affects your heart, your leg or your brain, it’s still an illness, and there should be no distinction.”

References available on request.

USEFUL RESOURCES

Below is a list of useful resources for readers. Do not forget, if you have immediate concerns about yourself, or someone close to you, dial 111.

The Mental Health Foundation: mentalhealth.org.nz

The Mental Health Foundation: mentalhealth.org.nz

Perinatal Anxiety and Depression: Aotearoa, pada.nz

Perinatal Anxiety and Depression: Aotearoa, pada.nz

Dr Isabelle Duck is a general practitioner and the clinical director of Silverdale Medical Urgent Care in Auckland. She lives in Hobsonville with her husband – a lecturer, and their daughter, Lauren.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 63 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW